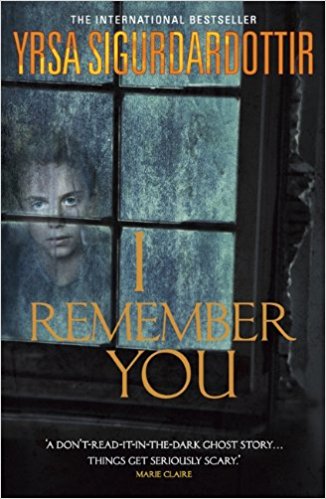

Having read Yrsa Sigurðardóttir’s novel I Remember You (Ég man þig) and seen the film adaptation, I found myself thinking about the theme of isolation.

A group of three adults head from Reykjavík to a remote outcrop of the Westfjords where they plan to do up an abandoned house and set it up as a B&B. The house is one of a few scattered buildings in all that remains of the abandoned village of Heysteri. Although not an island, it can only be reached by boat as there’s no roads over the mountain. In summer, it’s busy with visitors who want to climb or walk the hills and mountains that surround the area, but come winter and you are entirely cut off and alone.

In Ísafjörður, a boat ride away, lives a psychiatrist whose son has disappeared. His marriage collapsed in the face of their family tragedy, and he endures emotional isolation. He’s started to see what is either an apparition or a hallucination of his missing son. And a local woman, who was obsessed with the boy’s disappearance, has hanged herself in a church – which, it just so happens, had been moved from Heysteri and rebuilt.

Sigurðardóttir usually writes crime fiction, but even her “straight” crime fiction contains supernatural elements, be they a character’s fascination with seventeenth-century witchcraft, or the legend of babies who can still be heard crying on the rocks where they were left to die of exposure. There’s lots to learn by osmosis about Icelandic history, culture and traditions in her work.

So when I realised she had written a supernatural thriller, I was intrigued. I Remember You features a vengeful ghost intent on making those who tormented them in life suffer after their death. Whilst a murderer in a crime novel might be easily contained, the power of ghost stories, perhaps, is that the supernatural cannot be put safely away behind bars.

When I was a teenager, we moved to the Isle of Wight, and I always found Christmas Day profoundly uncomfortable as we were completely cut off. No ferries ran, so for an entire 24 hours we were trapped. Not long after we moved to the island, three dangerous prisoners escaped from Parkhurst Prison on the island. Knowing that we were stuck on an island with the prisoners running free was not exactly pleasant. Back in Essex, where I’m from originally, we were only a few miles away from Brightlingsea, a riverside town which had only one road in and out. Heavy snow could block the town off. During the 1803 Influenza Epidemic, Brightlingsea saw many deaths, whereas nearby villages didn’t – that long, isolating road effectively quarantined those who were infected, even if the flu possibly arrived in the town by sea.

Iceland is of course more isolated than the Isle of Wight. A third of a million people live on the volcanically active island just outside the Arctic Circle, and it’s the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Those sensations of being trapped, with a looming threat, repeat for me whenever I encounter Icelandic novels, films or television series. The obvious contender here is the amazing series Trapped (Ófærð), set in real-life Seyðisfjörður in the east of Iceland. A blizzard cuts the town off by road just as a mysterious torso is found in the fjord. Are the townspeople trapped in their snowbound settlement with a murderer?

Ragnar Jónasson sets his novels in Siglufjörður, another isolated town, which can only be reached by tunnels through the mountains. His novel Rupture opens with a possible contagion and the town is quarantined. A bored policeman starts to look through old cases, and becomes fascinated by an apparent suicide of a woman in a now-abandoned farm on a nearby, but hard-to-reach fjord. Did the isolation of the farm depress her, or was something sinister going on in that remote place?

I Remember You draws on similar themes, and those feelings of isolation and being trapped work just as well for horror and ghost stories as they do for crime. Even real-life crime can exercise fascination when it involves remote communities – the nineteenth-century press emphasised this when writing about the Essex Poison Panic of the 1840s. In crime fiction, the country house murder is of course the perfect example of this, and can be translated into similar environments, such as a snowbound train.[1]No prizes for guessing which Agatha Christie novel I’m talking about there. And of course, crime fiction has its origin in Gothic fiction,[2]Crime/ghost story cross-over writing never comes as a surprise! which is a non-stop rollercoaster of isolated castles, shadowy forests and abandoned ruins.

There are practical reasons why humans find being trapped in isolation so terrifying, but metaphorically it is very powerful too. A person can be more isolated in a city than in a community of ten people, after all. And that’s perhaps why Icelandic fiction which explores these themes can be engaging to readers anywhere. Just as much as the brightly painted snow-bound towns can provide escapism and armchair travel to readers, isolation is something we all can feel, wherever we live.