I was on holiday in Kefalonia as a child when I saw my first dead body: the rather wrinkly 16th century St. Gerasimus. He wasn’t on view for tourists, only for the eyes of the Greeks, but my grandad had spent so long faffing about with his Kodak that we were the last two tourists left in the church when his coffin was opened. He almost looked as if he was asleep, but it was hard to see if he was breathing under his thick velvet brocade gown. A monk chanted as a queue of penitents shuffled towards him, each kissing a velvet cushion placed over the papery saint’s feet. A little boy – about the same age as me – was lifted up so he could kiss the cushion. Having been raised Congregational, going each Sunday to a chapel which didn’t even have the mere suggestion of coloured glass in its windows – no statues, no gilding, and certainly no incorrupt saints – the spectacle fascinated me. Perhaps because my father was an undertaker (our family Volvo estate doubled as transport for “customers”), it had extra resonance, as if seeing St. Gerasimus helped me to understand what my dad did, dressed all in black with his very large umbrella.

Since that day, the concept of incorruptibles has fascinated me, so when I found out that Verity Holloway had written a novella about them, I knew I had to read it. Set in a not-too-distance future, as the world’s rising waters consume the land, St. Silvan is looked to as a symbol of hope by the residents of the drowning world. The pretty-boy saint travels by night, visiting other incorruptibles, including secular figures such as Lenin and an Anatomical Venus. A saintly Avon Lady, he recommends lipstick and powders to touch up the ancient figures. But as St. Silvan starts to remember who he was in life, the cracks start to show.

I spoke to Verity about her novella, her writing process and about her book The Mighty Healer, which is out later this year.

Which incorruptibles have you met “in person”?

So far, officially, just Saint Spyridon in Corfu. He’s a ‘walking saint’, so he gets up and goes for a stroll occasionally. He gets a new pair of slippers from time-to-time. I also wandered into a church in Venice a couple of years ago and came across a well-dressed but horribly desiccated corpse in a glass coffin. I don’t know if he was officially incorrupt, but I was fascinated by his little embroidered shoes, thinking he was probably from the Renaissance. Then I looked down and saw all the photos of him alive and shaking hands with John Paul II. I still don’t know who he was, or if he was officially incorrupt. The Church definition is quite nebulous – you can look like a dry prune and still be classed as a miracle. It’s not a straightforward term.

Do you have a favourite incorruptible?

Obviously, I’d love to see Silvan in person. He feels like my buddy now. I like St Catherine of Bologna. She’s a great example of how the definition of incorruptibility is quite loose. She’s been sitting there mummified for 500 years, on this amazing Baroque throne surrounded by gold and velvet. When the nuns exhumed her, she was said to be flexible and smelling of flowers. She’s gone black now, but she does look like she could just stand up.

Though they’re not incorrupt, I’ve been to the Capuchin Catacombs in Rome – there are about eight thousand monks interred there, and quite a few are attached to the walls, standing up in their cowls. They have light fixtures made of human bones – these cute little butterflies of skulls and pelvises. It struck me as creative and strangely playful. It’s interesting what monks and nuns will do for their own, in contrast to the gigantic gold edifices the Church set up for recognised saints. I do wonder what a nun like St Catherine would think of being surrounded by golden cherubs, with her vow of poverty.

You had to research the Roman period for your novella, for the backstory of St. Silvan. Anything particularly odd or unexpected that you found out?

Yes, the Romans aren’t really my ‘area’. I’m a Victorianist. so a lot of it was alien to me. The worst was the slavery. The things slave owners were allowed to do – in the book, I talk about contractors who would come to your house and crucify your slaves for you on your patio. That was real. All the instances of Roman violence were taken from real events. There was a soldier known as ‘Fetch Me Another’ because he was always breaking his staff over his men’s backs. I think what I found most disconcerting was how modern the slave owners sound in their own accounts – they sound just like nineteenth century slave-owners excusing their actions. Some of these people were Christians, too. Christianity didn’t immediately trigger reform.

How long did it take to write your novella? From initial germ of an idea to final draft?

I’d say from first jottings-down to complete, two years. It started on a boring Sunday afternoon when I was annoyed I had nothing to do. I made some notes about what an incorrupt saint would have to say for him or herself, and found that I wasn’t writing about religion at all. I work very slowly. When I look back after finishing, I don’t have a clue how I got there.

Do you have a favourite spot where you like to write? Do you have a preferred time of day for writing?

I have a room now, at the back of the house. It used to be a child’s room, so it’s bright yellow and covered in crayon scrawls. I’m trying to do it up, so now only a third of it is yellow and crayony and horrifying. The rest is white and lapis blue, and I’m filling the space with pictures and mirrors. I have an antique nursing chair I wrote most of Beauty Secrets in. It’s ragged and squishy. My most productive time for writing is night, which is inconvenient because I have Marfan Syndrome and chronic fatigue is a big part of that. I find myself rolling over in the night and scribbling something nonsensical down to decipher in the morning.

Do you have a preferred method? Type straight from your head, or write it longhand first before writing it up later? Do you write the whole thing before you edit, or do you edit as you go?

I type faster than I can write longhand, but I carry a notebook. And I edit as I go, which is a nightmare and really not the way to do it, but I can’t seem to do it methodically. Writing is like sculpting, for me. When it’s time for a major edit, I print the whole thing because it gives a very different perspective when in a different format. Sometimes I’ll use voice software to listen to it, see if the rhythms flow well.

Do you have any tips for other writers or would-be writers?

Read books you don’t want to read. Go to charity shops and spend a pound on something you’ve never heard of.

You decided to self-publish your novella. Did you feel it would be difficult to go the conventional route with a magic realist novella? What has your experience of self-publishing been? Has social media been helpful – or distracting?

I never wanted to self-publish, but I was in the middle of querying another novel and just wanted to get something out there. I looked at Beauty Secrets and thought, “Yeah, no, too weird” and decided not to query with it. Novellas tend to be more troublesome to publish traditionally. Social media has been useful, largely because there’s a big ‘histmed’ community, plenty of history nerds, and goths who already like incorrupt saints, anatomical Venuses, and the other creatures I’ve written about. The ‘death positive’ movement has been very welcoming.

Any writers you love who influenced – directly or indirectly – your novella?

Michele Roberts’ novel Impossible Saints. It’s really a series of magical short stories mingled together, about growing up female under Christianity during different points in history. I read it about ten years ago, and it was like nothing I’d ever read before. It made sense of a lot of feelings I didn’t consciously realise I was harbouring about my upbringing and identity. Magical realism can do that.

There’s a wonderful film called Beasts of The Southern Wild that got me thinking about floods in quite an obsessive way for a few years. I live in East Anglia, and we’re so flat, we’ll be some of the first land to go as the sea continues to rise. It’s quite a mysterious area of the country. There’s a long history of mystics and martyrs here, and that’s sunk into me over the years. Julian of Norwich bricking herself up and writing about unending love. The landscape does seem to foster that sort of extreme behaviour.

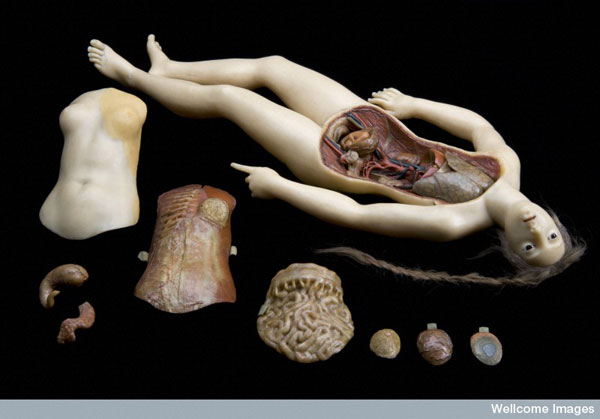

Ever since I’ve known you, you’ve been fascinated by medical history, so the appearance of the Anatomical Venus in your novella didn’t surprise me at all – she’s a perfect cross between the incorruptibles and medical science, emphasising the sexual frisson of the supine, available body of the dead saint. Have you seen one on display?

I have seen one in person. She didn’t have any legs, or a head. I think she was created to display the uterus, but wasn’t given a head because the students wouldn’t like her looking them in the eye. There’s something very Freudian about that. At the same exhibition, there was a little boy – a real one – who had been skinned and preserved in the eighteenth century (I think), and he had less of a presence than the Venus.

She’s got a benevolent feel to her, whereas the boy had vacated his body and his parents donated it. The Venuses give you permission to be fascinated without having to keep up a veneer of respect. You’re allowed to be openly fascinated in a voyeuristic way that verges on sensuality. They don’t need to be beautiful, but some of them have jewellery and elaborately styled hair. Would you do that to a medical cadaver? That’s why I find them so compelling.

I enjoyed the appearance of Lenin in the novella. It reminded me a bit of the novel Santa Evita, about Evita, but also the journey of her embalmed corpse (not, sadly, that she reanimates!). Do you think that Lenin (or his followers) created a substitute for Eastern Orthodox Christians with Bolshevik art and the veneration of his corpse?

Lenin just turned up of his own accord. He was rude and confrontational as a character, and quite troubling as an object – why would you display a corpse like that without a scientific or spiritual reason? But it is spiritual, really, I think. Political devotion as cult, perhaps. There seems to be a human need to preserve the dead, or display them somehow, and I love that the Communists laid Lenin out like a saint.

They’re struggling to keep him pretty, too, so I watched a long video of Russians in white coats lovingly undressing him and dipping him in some sort of green liquid. I came across a lot of sneering online about incorruptibles and the religious preservation of the dead, but really, most cultures do it in some form or another, for so many reasons. It’s considered primitive now in Western secular culture, but the death positive movement is trying to normalise the presence of the dead again. Memento mori is a healthy thing, I think.

Have you had a pet clownfish yourself?

No, but I have quite a few catfish. Marcel the Plecostomus is like a dinosaur. They can scream by rotating their bones, if they feel threatened. (I’ve never heard Marcel scream, and I think I’d pass out if I did!) The clownfish arrived as a nightmare, actually, while I was editing the novella. I was walking down the promenade on a very grim British seaside resort and saw all these flapping orange fish on the shingle. Seemed a shame to waste them.

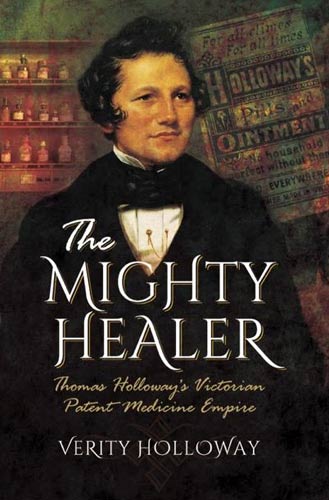

You have a book out next year about your famous relative, Thomas Holloway. Can you tell us more about that?

The Mighty Healer is about my Victorian cousin Thomas Holloway who made millions with patent medicine. It’s my first non-fiction book. Thomas grew up in a Cornish pub, experimenting with his mother’s leftover cooking grease, and it made him one of the richest self-made men in the Empire. Holloway’s Pills and Ointment were just inescapable in Victorian England and beyond. Dickens joked about him. Thackeray publically ridiculed him. He had a billboard beside the Pyramids and called himself Professor. Surprisingly, for a quack doctor, he used his millions to build a progressive insane asylum and one of the first colleges for women. He’s a contrary character. It’s out in Autumn 2016, with Pen & Sword.

Are there any more novellas or novels in the pipeline?

I’ve got one magical realist novel that I’m finalising at the moment, and one historical novel that’s been sitting on the backburner for a while. I think I’ve got saints out of my system, for the time being. Probably.

Find out more about Verity Holloway:

Beauty Secrets of the Martyrs is available in paperback, from Amazon UK and Amazon US, as well as Waterstones (you can have your Waterstones order sent to your house or you can collect it. You can also order it in person at your local branch). An ebook version is forthcoming.

Comments are closed.