Having travelled to Rugeley and to Edinburgh in pursuit of Alfred Swaine Taylor for my book Fatal Evidence, it was time to go to London and Kent. He was born in Northfleet, Kent, on the banks of the River Thames in 1806, and eventually moved to London, where he stayed for the rest of his life (trips back and forth to inquests and trials across England notwithstanding).

We got off the train at Euston, and headed straight for the church of St Pancras on Euston Road. I was once lucky enough to tool around the vaults under the church, which had been decked out for an art installation. It was spooky and fun and there were some fantastic memorial slabs down there. But alas, I hadn’t checked in advance – St Pancras is closed on Fridays! So we couldn’t go in, which is a shame as there was, and perhaps still is, a plaque on the wall memorialising John Cancellor, Taylor’s father-in-law. Taylor married Caroline Cancellor in the church in 1834, and both their children were baptised there.

The next stop on our dash around the south-east was to go from St Pancras to Taylor’s home on Regent’s Park. We took the tube from Euston Square, which is ironic as it’s right next door to the frontage which doubles as “Baker Street” in BBC Sherlock (we’d been to London a couple of weeks earlier, the morning after scenes from series four had been filmed there – it still had the fake street sign up saying Baker Street to cover its actual name!).

Working out exactly which house on Chester Gate (formerly Cambridge Place) that Taylor lived in is impossible. On the 1841 and 1851 censuses, the baptism records of his children, and on correspondence of his which was published in newspapers and in his books, his address is given as 3 Cambridge Place. It’s also the address of his wife’s brother, Richard, when he wrote his will in 1833, leaving the lease of Cambridge Place to Caroline. But where is number 3?

First of all, identifying Cambridge Place itself is a mission as it’s been renamed Chester Gate. But without a street plan showing house numbers from the mid-19th century, it’s impossble to know which house Taylor lived in, as the street could well have been renumbered since then.

So first of all, this photo – the house with the projecting, angled corner, seems to be number 3 today. Was it Taylor’s house? If you look closely, that woman in her rainmac[1]aka me is in shot, heading down the side of the house to look for a garden. I can imagine Taylor looking out from one of those windows, rising and falling on the balls of his feet as he puzzles out a problem. Such as… how can he improve on Fox-Talbot’s photography experiments? How can he demonstrate to a jury how arsenic poisoning works? Or perhaps he was composing an acerbic few lines for The Lancet, about Henry Letheby.

But that might not have been his house. So here’s another shot of Chester Gate, taken from a spot just to the left of the photo above.

Somewhere in one of these photos is Professor Taylor’s former gaff. And also, look closely and that woman in the mac is photobombing again.

After 1851, Taylor moved across the park to St James’ Terrace. It was knocked down in the 1930s and replaced with a block of art deco flats that Poirot would be glad to call home. Lovely as it is, there wasn’t much point visiting that side of the park.

Just around the corner from Chester Gate is Albany Street, where the blue plaque commemorating Henry Mayhew can be found. Taylor and Mayhew had a public falling out during the William Palmer trial, when Mayhew put Taylor in a very compromising position. Just how pleased is the shade of Taylor about Mayhew’s blue plaque being so close to his former home, especially when Taylor himself doesn’t have one? I hope he’s suitably irate.

We hopped back on the tube and headed east, to St Pancras station and the fast train to Ebbsfleet International.

Once at Ebbsfleet, despite me trying to work out how to walk from the station to Northfleet via the medium of Google Streetview, staff at the station said, “Just get a taxi.” And looked a bit surprised that I’d even considered the attempt. So we were off to the town of Taylor’s birth. First of all, we went to the church where his parents were married in 1804, and where he and his brother Silas were baptised. I was lucky to have found transcriptions of the family gravestones online thanks to the Kent Archaeological Society – they give invaluable information, such as informing us that his father was from King’s Lynn in Norfolk, and that he was a Captain in the East India Company. Not that I’ve been able to find Thomas Taylor in the EIC’s records, but he did eventually become a flint merchant – the land around Northfleet being rich in flint.

I wonder if the headstones have been moved from their original positions? But on the left, we have the grave of Taylor’s parents, and on the right, with the more elaborate top, Taylor’s maternal grandparents.

His parents’ headstone reads (or at least used to) :

Mrs Susan Taylor Obt Decembris 8th Anno Domini 1815 Aet 37.

She was worthy of example as a Wife a Mother and a Friend. Go thy way passenger and imitate Her whom you will some day follow.

Also in memory of Thomas Taylor late of the Hon. E.I. Company’s Maritime Service. He was born at Lynn Regis, Norfolk September 23rd 1771 And died at Northfleet September 28th 1840 Aged 69.

“Filii Morientes Posuerunt”.

The engraving on the stone on the right has survived better, and reads:

In Memory of Mr Charles Badger (of this Parish) who departed this Life the 25th of March 1800 Aged 31 years.

Left issue three dau. (viz) Susan, Eliza and Harriot.

“I’ve had my part of worldly care/When I was living as you are/But now my body lies in dust/Until the rising of the Just”.

Also Mrs Mary Badger wife of the above who departed this Life 18th of June 1834 Aged 81 years.

Although I haven’t found any clue as to where Taylor was born or where he lived in as a boy, we do know which house his father lived in at one point. It appears in adverts for his business in the 1830s, and finally on his will written in 1835 – number 1 Granby Place. So I found Granby Place, but wasn’t sure which side would have been number one! Perhaps the left half? I don’t know. It’s not as grand as Taylor’s Nash terrace in London, but not a shabby residence by any means.

It was time to leave Kent for London once more, so we zoomed back into town on the fast train to St Pancras, then ate some weird thing that was a bit like a Scotch egg outside the station.

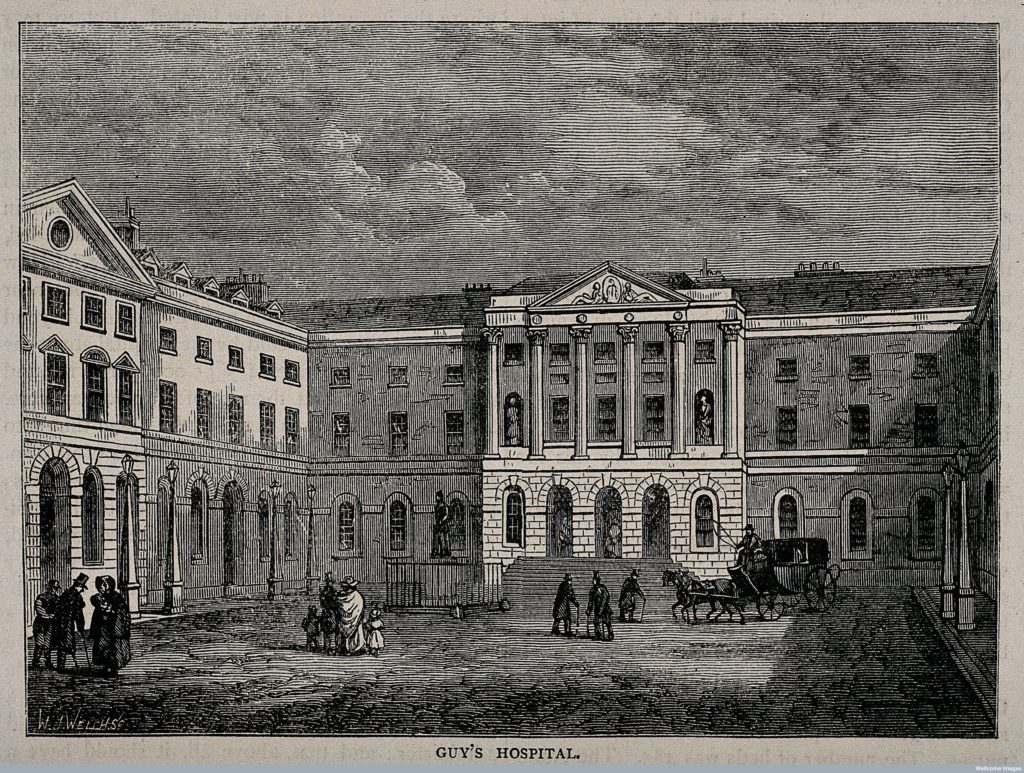

Off down to the south of the river to Guy’s Hospital next, where Taylor was a student, and where he spent his entire working life. He was made chair of Medical Jurisprudence (the intersection of medicine and the law, which includes forensic medicine) in 1831, aged 24, and finally retired from the post in 1878.

When we arrived at Guy’s, popping out of the earth at London Bridge station, I was taken aback when I found myself at the foot of The Shard. I’d seen it in the distance before, but to find myself staring up from the foot of that ridiculous monstrosity did rather take me by surprise. The courtyard of Guy’s is just across the road from The Shard, and it was in the middle of massive building works, so I couldn’t capture a “then and now” photo of it, although you can see one wing of it below.

It was very busy, and very loud, so we didn’t linger. We went down Great Maze Pond, the road which runs through the hospital campus, and came out on Snowfields. Why, you may wonder, did we go down there? Because back in 1876, my great-grandmother was born in a hovel on that street, and I’d never visited it. It’s strange to think that for a couple of years, she lived so near to Taylor’s place of work. I doubt they ever met, however!

By now, we needed lunch, so we headed to the Sherlock Holmes pub, just off Trafalgar Square. At the 1951 Great Exhibition, there was a Sherlock Holmes display, recreating (or perhaps “creating”…) his lounge, with bottles of chemicals and test-tubes on his shelves. Once the Exhibition closed, the Holmes display took up residence in the pub. Given that I wouldn’t be at all surprised if a little bit of Professor Taylor made it into the character of Holmes, this pub seemed to be the most appropriate place for lunch. I was having a fantastic, geeky time.

We were now on the final strait, and went to St James’ church in Piccadilly – this is where Taylor’s only son was buried in 1836. By then, he and his wife were living on Cambridge Place, off Regent’s Park, so I don’t quite know why their son was buried there. However, before his marriage to Caroline, Taylor had been living at 35 Great Marlborough Street in Soho, which is in St James’ parish – at the other end of his road, was St James’ Infirmary, where he chummed up with the resident surgeon, John George French, and the physician Dr John Snow[2]The Broad Street pump guy, who was the first person to realise that cholera was water-borne. That, or there is some as-yet undiscovered familial reason to explain why the little boy was interred there.

We reached the church from Jermyn Street, legendary for its gentleman’s outfitters. It seemed appropriate to be only feet away from Floris – perhaps Taylor used to douse himself in their cologne to take his mind off the “delightful” subjects in his laboratory.

We went to Great Marlborough Street, but it’s a very difficult road to photograph. Libertys might look quite old, but it’s not a building that Taylor would have recognised in the early 1830s. But just think – nearly 200 years ago, Taylor walked along this very street – even if the buildings were different!

One last visit before we headed back to Euston – the home of Taylor’s brother, Silas, in 1841. He lived on Regent Square in Bloomsbury. Three sides of the square were destroyed by the Blitz, so only one terrace of houses remains to remind us of what old London – the London of Alfred Swaine Taylor – would have looked like.

If you were to drop into the photo immediately below and head up to the top of the square, on the left is a church where once stood the house from which “female impersonators” Fanny and Stella were arrested. This was one of Taylor’s last famous cases, when he was asked to perform a rather uncomfortable examination of Fanny and Stella, to determine whether or not they had been enjoying “the delights of Plato”, shall we say. I can’t think that was much fun for anyone concerned, but it generated lots of pamphlets because the general public are ever prurient. One of them found its way into Taylor’s collection, which is held by the Royal College of Surgeons, just around the corner from his old house on Cambridge Place.

It had been a long day, and we were ready to stumble back to Euston station, but I spotted on the wall of one of the Regent Square houses an old medicinal advert that is reviving. Appropriately, whatever the long-gone product was, it promised to cure “Wounds & Sores.”

We had a very busy day, and I didn’t count up how many miles we did, but factor in a train journey there and back from Birmingham and we really did pack a lot in. But it gave me an appreciation for the locales that Taylor would have been familiar with, even if they have changed quite a lot from his day. No Shard by Guy’s Hospital then, nor high-speed trains to Ebbsfleet. But still, where the buildings remain, I felt as if I had come a bit closer to Taylor, and as his biographer, that could only help to bring him back to life.