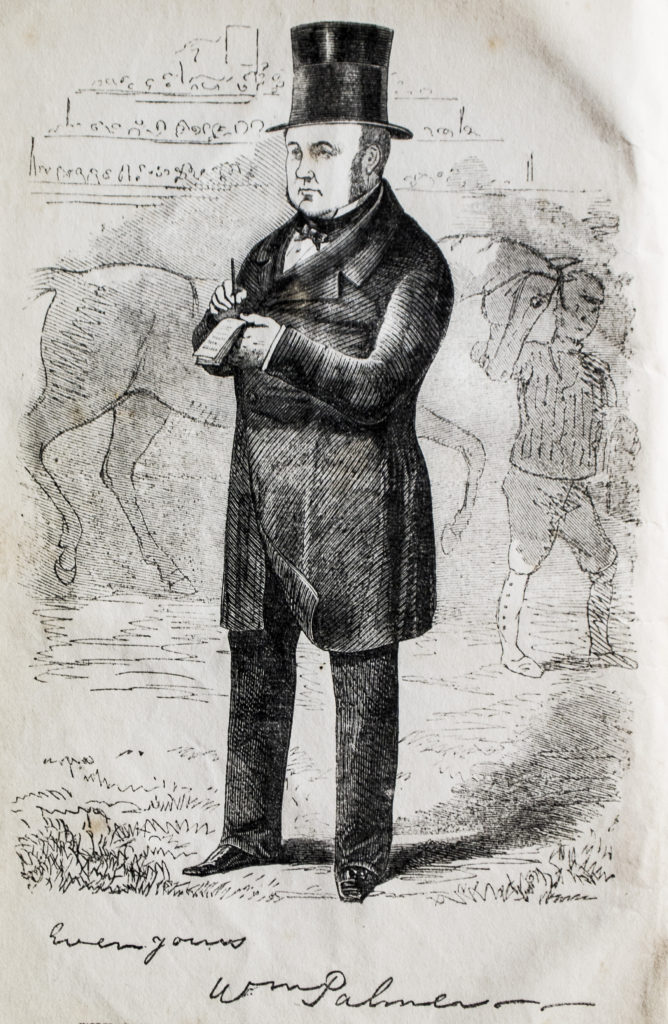

One of Alfred Swaine Taylor‘s most famous cases was that of William Palmer, The Rugeley Poisoner. As I live in the West Midlands, Rugeley isn’t all that far from me, so I decided to pay the town a visit.

I felt rather awkward, because poor old Rugeley probably doesn’t want to be remembered for Palmer and his ‘orrible crimes. In 1856, as Palmer stood trial and the newspapers bulged with reports about him, journalists[1]It’s thought that novelist Wilkie Collins was amongst them. were dispatched to the unassuming market town to write lurid pieces about the locality. The Illustrated Times helpfully published a special supplement, full of Rugeley scenes – some of which you will see in this very blog. Members of the public visited just to see the place they’d read so much about. The local vicar had so many people trudge to his churchyard to see where John Parsons Cook, one of Palmer’s victims, was buried that he paid for a gravestone, bearing moralising quotations from Scripture: Enter not into the path of the wicked.

As the town hall where the inquests took place has been rebuilt, the first place connected with Palmer that we arrived at was the Talbot pub. This was where Cook was poisoned, and where he died.[2]I realise that some people don’t think Cook was murdered, but I am not of that opinion. We couldn’t go in as the pub – last called The Shrew – has closed down. However, directly opposite was Palmer’s house. Not that you can see very much it of these days – in Palmer’s time it had a front garden, but eventually the front was extended out to touch the road, and it’s been divided into two shops. You can get round the back though, and that view hasn’t changed all that much.

I walked back and forth between the pub and the shops a couple of times, to get a feel for Palmer’s own journeys, back and forth between his house and the man he killed. It’s not a vast distance at all, being only the width of the road. I paused, and looked up at the window of the room where Cook died. After writing Poison Panic, where poisoning victims died in cottages that are either long gone or can no longer be identified, it felt very strange to be able to almost come to the exact spot where the crime had taken place.

My partner, who takes many of the photos in my books, photographed the streetscene, and it’s interesting to compare Rugeley in 2016 with Rugeley in 1856. It’s not quite as busy as it was, and I somehow doubt the Union flag bunting is there to celebrate the spot where a famous British murder took place. At least, I hope not!

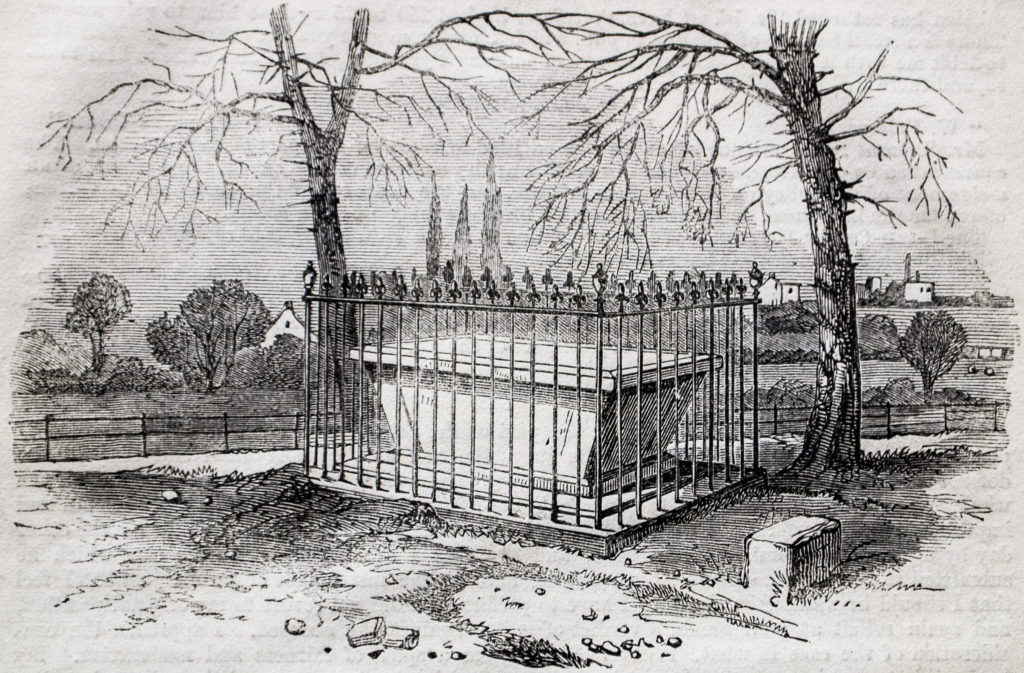

Our next stop was the church of St Augustine, where John Parsons Cook is buried. A terrible sensation that I was intruding had haunted me since I got off the train, but once I saw that the information board outside the church actually tells visitors where to find Cook’s grave in the churchyard, I felt slightly less ghoulish for my interest.

As with the houses and cottages of Poison Panic, I had never been able to visit the last resting place of the people as they are no longer identified: no headstones are in Wix, Tendring or Clavering for the victims of arsenic poisoning. So standing beside John Parsons Cook’s grave was a very poignant moment. I don’t know for sure, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that tree behind me in the photo appeared in the engraving that appeared in the Illustrated Times, below.

The Palmer family tomb is at the back of the church. William Palmer himself isn’t buried there as he was buried at Stafford gaol, where he was hanged. Part of the sentence for murder was the ignominy of an unmarked grave where prisoners walk by.

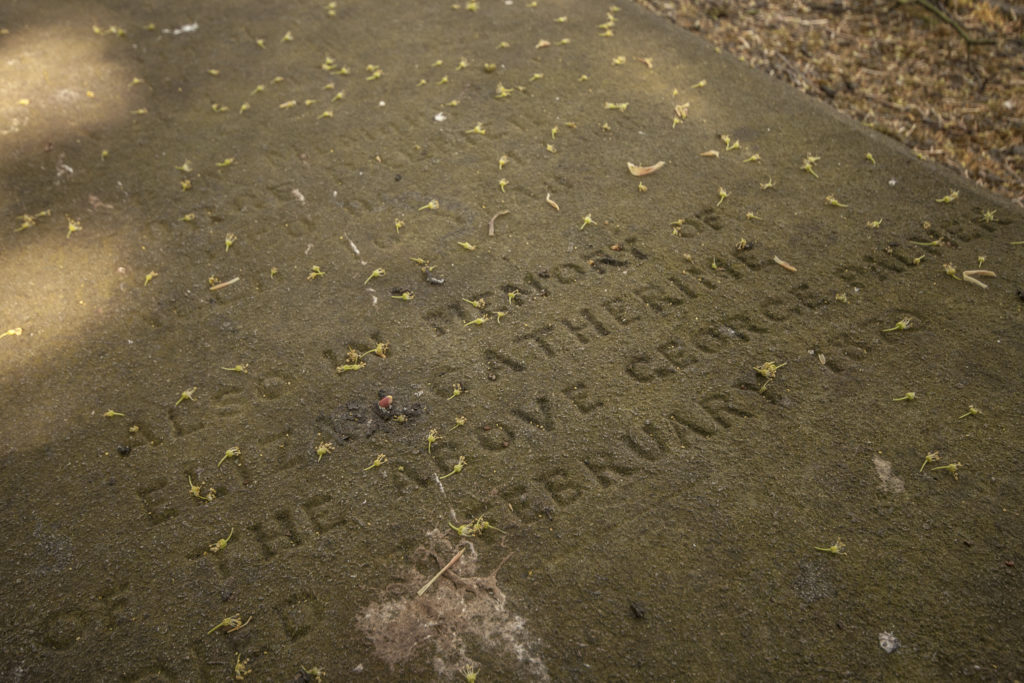

What was interesting about this grave (allow me to turn genealogist for a moment) is that at one point it was a box tomb, with fancy railings, but the sides gave up at some point and the railings disappeared – all that we’re left with is the top. I wonder how many other graves which now exist only as a slab were once box tombs?

And to head off angry complaints – I knelt on the grave very gingerly, in order to read the inscriptions on it. No disrespect is meant to the grave’s residents. If anything, trying to read the names of those buried there is to remember them, not disrespect them.

We went inside the church – I have always enjoyed visiting churches – and was happily wandering about when a local parishioner decided to chat with us. I didn’t explain why I was in Rugeley, but she suddenly mentioned: “We got rid of the old pews in the late 1800s.” She pointed towards the middle of the church. “We had a poisoner, you see, and his family pew was there.”

A chill went through me. But the moment to state my interest in Rugeley’s poisoner passed. I nodded. “Oh, yes, I believe I’ve heard of him.”

“You would have passed his victim’s grave outside the door.”

I nodded, smiling. I just hoped she hadn’t seen us stood by the grave earlier. Or popping round the back to look at the Palmer family tomb. Sorry, nice lady.

The house where William Palmer was born, and where his mother was living at the time of his trial, is across the road from the church where the John Parsons Cook and the Palmers were buried. It is said she would run out of her front door, shouting at the sightseers who gathered by her gate – “they hanged my saintly Billy!” So once again, I felt rather naughty turning up at the house, as if my presence would reawake his distressed mother. But I couldn’t go to Rugeley and to the church directly opposite and not see it. The Illustrated Times showed the house from behind, presenting an idyllic view which perhaps didn’t really exist even at the time the artist drew it. The waterway was used by Palmer’s father for his wood merchant business, to transport stock. Palmer’s home did once overlook fields, which are now full of houses.

Beside the Palmer house is Rugeley’s old church. The tower still exists, and arches, as well as part of the nave, which is locked and appears to be used as storage these days. There are some fascinating old tombs in the churchyard – you can see my favourite below, which shows how people were wrapped for burial in their winding sheets. A window in the side of the Palmers’ old house looks down over the tomb – imagine growing up seeing that every time you looked outside.

The feeling of disquiet I experienced in Rugeley must have played on my mind. That night, I had a horrible dream. I was in the churchyard, by John Parsons Cook’s grave. The light was grey, as if at twilight or during a eclipse, and all I could hear around me were the incessant, whispered words from the Lord’s Prayer: Deliver us from evil, Deliver us from evil.

But my other trips in the pursuit of researching Alfred Swaine Taylor’s world, would take me further afield – to London, and to Edinburgh.