Warning: for spoilers and dead people.

Television series Endeavour tells the adventures of young Inspector Morse, when he was mere Detective Constable Morse. I was late coming to this programme, but I have become completely addicted to it. Perhaps it’s the slightly grubby vision of the 1960s that fascinates. Perhaps it’s the puzzling plots. Perhaps it’s the portrayal of young Morse by Shaun Evans, who manages to include John Thaw mannerisms in his characterisation without looking as if it’s an impression.

There’s lots to love about it but one episode caught my attention particularly – “Nocturne”, in the second series.

Set in 1966 during the World Cup, there are flashbacks to 1866, when several children of a tea magnate, their nurse and governess, were murdered. Everyone thinks the murderer was the surviving daughter, who was, apparently, disturbed, and ended her days in an institution.

My interest was immediately piqued – nineteenth-century crime! – and when I heard the music, which was played on the piano and on the world’s creepiest music box, and was woven through the background music, I recognised it at once.

The piece of music is Chopin’s Nocturne no.1. It’s a beautiful piece for piano but it is intensely creepy and unnerving. It’s in B flat minor, which goes to some way to explaining it, plus the way that it keeps reaching for resolution and takes a surprising direction keeps the listener on the alert. This seems to be something to do with “picardie thirds” but that’s another story. It’s often peddled as a relaxing number – but I find it’s quite the opposite. It’s calm, but discordant, which makes it terrifying.

It was for this reason that last year, without having seen that episode of Endeavour, I used exactly the same Chopin piece for the Poison Panic book trailer.

So I’m not the only person to hear that nocturne and think of Victorian murder.

It should be obvious to anyone with even a passing interest in nineteenth-century crime that the 1866 murders in “Nocturne” are based on the 1860 murder of Francis Kent, which everyone and his dog knows about thanks to Kate Summerscale’s The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. The murdered child’s sister, Constance Kent, confessed to the crime in 1865. That the crime in “Nocture” should so resemble the Road Hill House case is no random coincidence, but was quite intentional as Russell Lewis, who writes Endeavour, worked on a dramatisation of the case in the 1970s.

Nineteenth-century murder cases aren’t uncommon in the land of Inspector Morse. While writing Poison Panic, I took a week off work to focus on my book, and one lunchtime decided to watch an Inspector Morse repeat. And what should Morse be doing in this episode? Why, he had taken time off work and was investigating a nineteenth-century murder.

“Nocturne” was such a brilliant episode – referencing a real-life case, and filling a spooky old school with ghostly goings-on (it even reminded me a bit of my junior school). So I do feel a bit mean pointing out a rather glaring error:

Crime scenes were not photographed by police in the 1860s.

It makes excellent television, and television is a visual medium, of course – the stiff police standing about while the photographer works, the crime scene photos of bloodied bodies in period costume, Morse watching a lantern-slide show of the photographs. But this just didn’t happen in 1866. Crime scene photography began to evolve in the late-nineteenth-century, but 1866 is too early.

How do I know this? Well, Alfred Swaine Taylor, who you can read all about in his biography, Fatal Evidence, was a nineteenth-century forensic scientist who, in his spare time, fiddled about with photography.

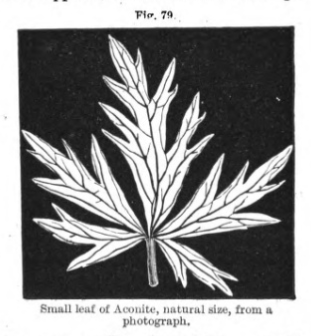

Taylor didn’t have much spare time, as he was busy working on cases and writing books and articles about “medical jurisprudence”. You would think that a man like Taylor, who used ‘photogenic drawings’ in his books to show readers what poisonous plants looked like, would have loved the idea of crime scene photos. But in the 1866 edition of his Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, he mentions photography only once: when writing about potassium cyanide causing “serious effects” when coming into contact with the skin. He doesn’t say anything about photographing crime scenes.

In 1873, his Principles and Practice of Medical Jurisprudence included over 200 illustrations. Amongst them was a diagram of a crime scene. This showed the 1862 murder of Mrs Gardner, wife of a chimneysweep, who had been found dead with her throat cut, a knife left loosely in her hands. It looked like suicide, but was it?

The wounds were not of the sort that one could administer oneself. Additionally, Dr Sequiera, the ‘medical gentleman’ who had been called in when the body was discovered, had sketched the position of the body, as well as the knife cuts to Mrs Gardner’s hands. It was evidence which helped to show that it was in fact a murder which had been made to look like a suicide.[1]I have decided not to reproduce the images here. Although it is a drawing rather than a photograph, the image itself might be upsetting for some. It’s possible that Mrs Gardner was found naked … Continue reading

Taylor praised Dr Sequiera for his sketches. Had Dr Sequiera taken a photograph, Taylor would have been over-the-moon, one suspects. He may even have turned a cartwheel, whipped off his cravat and swung it over his head.

So… nope… as much as I loved the “Nocturne” episode of Endeavour, the crime scene photos just wouldn’t have happened.

However, I do concede that it made far better television than showing a ‘medical gentleman’ sat there with a pencil.

**Stay tuned for me getting very uppity indeed about the arsenic analysis in BBC’s historical Tom Hardy drama Taboo**

Footnotes

| ↑1 | I have decided not to reproduce the images here. Although it is a drawing rather than a photograph, the image itself might be upsetting for some. It’s possible that Mrs Gardner was found naked and that someone partially covered her body before Dr Sequiera made his sketch. |

|---|