At depth of night, this thought on home had shone;

‘Our distant child draws safe his sleeping breath.’

E’en then the cherish’d boy, th’ expected son,

Was dying through two hours – beaten to death.

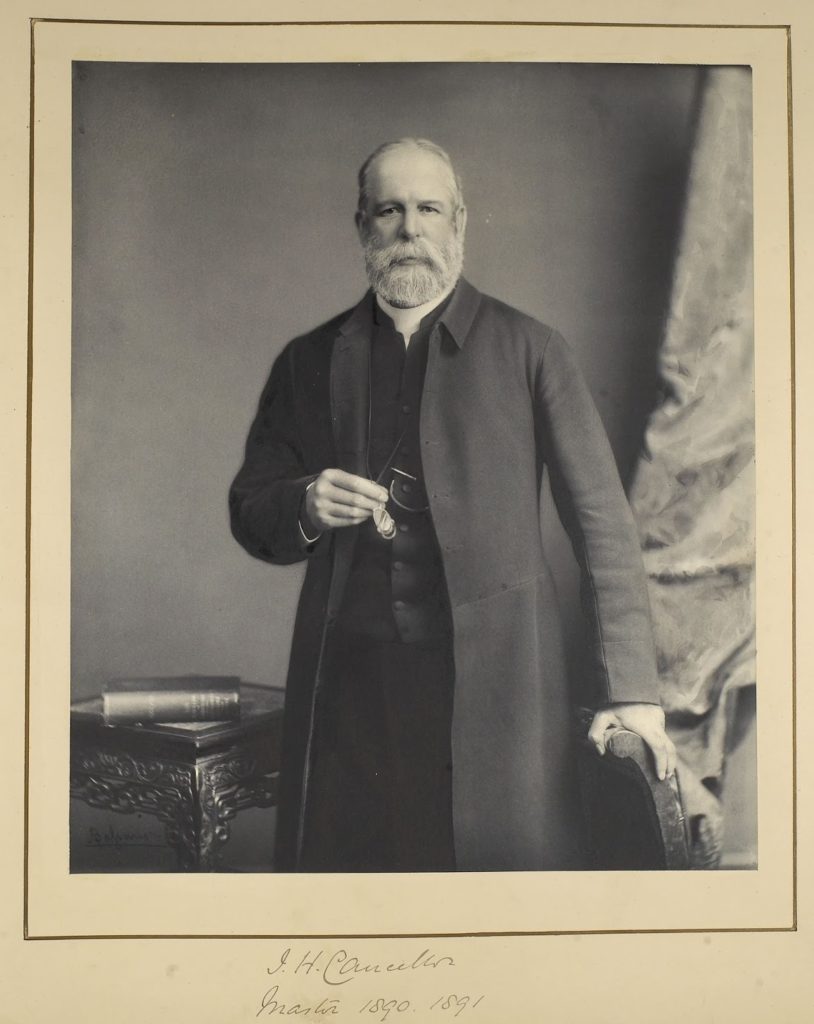

Reverend John Henry Cancellor was born in London in about 1834. His father, another John Henry Cancellor, was a Master of the Court of Common Pleas, and his grandfather had been a stockbroker. The family moved in monied circles.

Life was not plain-sailing, however. In 1856, Rev. Cancellor’s bankrupted uncle, Ellis Cancellor, tried to commit suicide by throwing himself into the Serpentine. And Rev. Cancellor’s youngest sibling, Reginald Channell Cancellor, “a particularly kind and affectionate boy, and very much attached to his father,” had what we would now call learning difficulties.

Rev. Cancellor was ten years older than his brother, so when, in late 1859, fifteen-year-old Reginald’s schooling became a problem, the older brother could step in with advice. Rev. Cancellor had been ordained as a deacon in 1857; as a respectable gentleman and a reverend, he decided to make use of his connections to help his parents school his brother.

He received a recommendation for Thomas Hopley’s school in Eastbourne. Hopley had grand ideas on educational reform; he had studied the education of industrial workers, and had written books on the subject. If anyone could manage Reginald, a boy who was seen as stubborn and lazy, who “would not readily do what he was told,” then surely it would be Hopley. And so Reginald was sent to Eastbourne.

Hopley didn’t like to use discipline on his pupils, unless it was deemed absolutely necessary. And with Reginald, it seemed that Hopley reached the end of his tether. When Reginald came home for the Christmas holidays, his father complained that too much violence had been used on him, but he did think that Reginald’s demeanour had improved.

In April, a letter arrived at the Cancellors’ home from Hopley, saying that Reginald had become obstinate again – and that he recommended the use of “extreme punishment” to force a permanent change in the boy. Hopley didn’t have a cane because ordinarily he didn’t like to use violence, so when Reginald’s father approved Hopley’s idea, the schoolteacher had to improvise.

With a walking stick and a skipping rope.

The day after inflicting “extreme punishment” on Reginald, the boy was found dead in his bed.

Reginald’s heartbroken father arrived in Eastbourne, to find the boy laid out, washed and carefully dressed so that only his face showed. Hopley had hired a surgeon, who told Reginald’s father – based on information from Hopley – that the boy had died of heart disease. Cancellor believed his word. Perhaps guiltily, he asked if “any slight punishment” could have killed his son; the surgeon said no.

The surgeon’s opinion went unchallenged at the inquest, but rumour was afoot courtesy of Hopley’s servants, who had heard screaming and had seen blood on the floor. The nursemaid knew the sister-in-law of physician Sir Charles Locock, who counted Queen Victoria amongst his patients. The nursemaid wrote to Locock and he intervened – he knew the Cancellors. Hopley visited Locock and asked him to help clear up the rumours by issuing a certificate to say that Reginald had indeed died of heart disease. Hopley admitted that he had beaten the boy, so Locock asked him about the blood that had been seen. The headmaster “turned pale, and made no reply, and, after standing still for a minute or so, he took up his hat and went out of the room.”

Enter the Reverend

Reverend John Henry Cancellor, travelled down to Eastbourne with an undertaker, to collect his brother’s body.

The family were clearly dissatisfied with the explanation for poor Reginald’s death, and it might have been Locock’s involvement which meant that Rev. Cancellor could tell Hopley that there would be a post-mortem after all.

Then Rev. Cancellor quizzed him. Had Hopley drawn blood? Had there been any noise after 10pm? Why had he told his father that Reginald had been happy after the punishment? Hopley showed him Reginald’s body, lying in a lead coffin, and Rev Cancellor asked him what the mark was on his brother’s face – was it a bruise? Hopley denied it, saying it was normal discolouration after death. Standing over the coffin, Hopley “clasped his hands together and said, ‘Heaven knows, I have done my duty by that poor boy.'”

If Rev. Cancellor’s questioning sounds out of place, this is because he was no ordinary clergyman. His uncle was Alfred Swaine Taylor, one of the leading forensic pathologists[1]Taylor called himself a “medical jurist”. His wife, Caroline, was the sister of John Henry Cancellor senior. in the land.

None of the information in public on what became known as the Eastbourne Manslaughter ever mentioned Taylor’s name, nor his family connection with the victim. But in Cancellor’s questions, I think we can see the shadow of Taylor’s hand. With Locock involved, Taylor must have become drawn in too, as Reginald was, after all, his nephew. Taylor could not help but be interested in medico-legal cases, even when he was not hired as the expert witness. When the truth of his own nephew’s death was under scrutiny, then it would have been out of character for him not to have taken an interest, difficult as it may have been. The questions that Rev. Cancellor, asked Hopley appear to bear Taylor’s stamp.

Tragedy

On 22 June 1860, just before the case went to trial, Reginald’s father died. He was 61 years old. It is quite possible that the stress of the investigation, his bereavement and perhaps even his own guilt led to his death. His wife passed away less than two years later, perhaps never recovering from what had happened to their son.

This left Reverend John Henry Cancellor to be the witness who would not only relate his meeting with Hopley, but also what he recalled of his father’s actions.

Hopley was found guilty of manslaughter. Lord Chief Justice Cockburn was the judge at Hopley’s trial, and his definition of reasonable force set a legal precedent. The headmaster was universally loathed – the case even inspired the quite awful poem called “Beaten to Death” quoted above – and Hopley’s own defence counsel, William Ballantine, doesn’t appear to have made much effort to defend him. Taylor was too close to the case and wasn’t involved in an official capacity; Ballantine, however, was a friend of the Cancellors and so struggled to be objective.

Taylor was forced into a corner. It was never publicly known that he had a familial connection to the case that so horrified the Victorian public. But poor Reginald’s fate was so well-known that, when compiling legal cases for his books on medical jurisprudence, he couldn’t omit the story of the Eastbourne Manslaughter.

Even though it must have been incredibly painful to write about his nephew’s horrific death, Taylor could at least be proud of his ecclesiastical nephew. His quizzing of Hopley, and later his testimony in court, was confident and assured. The presence of such a man in the witness box, who was more used to a pulpit, may have have lent extra credence to the case against Hopley.

Read more about the Eastbourne Manslaughter in Fatal Evidence, my biography of Alfred Swaine Taylor.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Taylor called himself a “medical jurist”. His wife, Caroline, was the sister of John Henry Cancellor senior. |

|---|