Alfred Swaine Taylor and the arsenic in the wallpaper

When “used” is “new”

My second book was published on Monday. The copies arrived with my publisher on the Friday before.

So imagine my surprise when, only a couple of days later, two third-party sellers on Amazon were selling copies “used – as new.”

This is physically impossible. There are no used copies, because readers and reviewers are still receiving their copies of the newly published books. So where are these “used” copies coming from?

This happened, too, with my first book, Poison Panic, which was published last year. Confused, I had contacted the sellers, and without replying to me, they changed their listings to “new”. At the time, I talked to my writing friends about it – the self-published authors I know find it particularly odd: “I haven’t even had my copies yet – where are they getting them from?!”

Real-life ecclesiastical sleuths: Reverend Cancellor & The Eastbourne Manslaughter

At depth of night, this thought on home had shone;

‘Our distant child draws safe his sleeping breath.’

E’en then the cherish’d boy, th’ expected son,

Was dying through two hours – beaten to death.

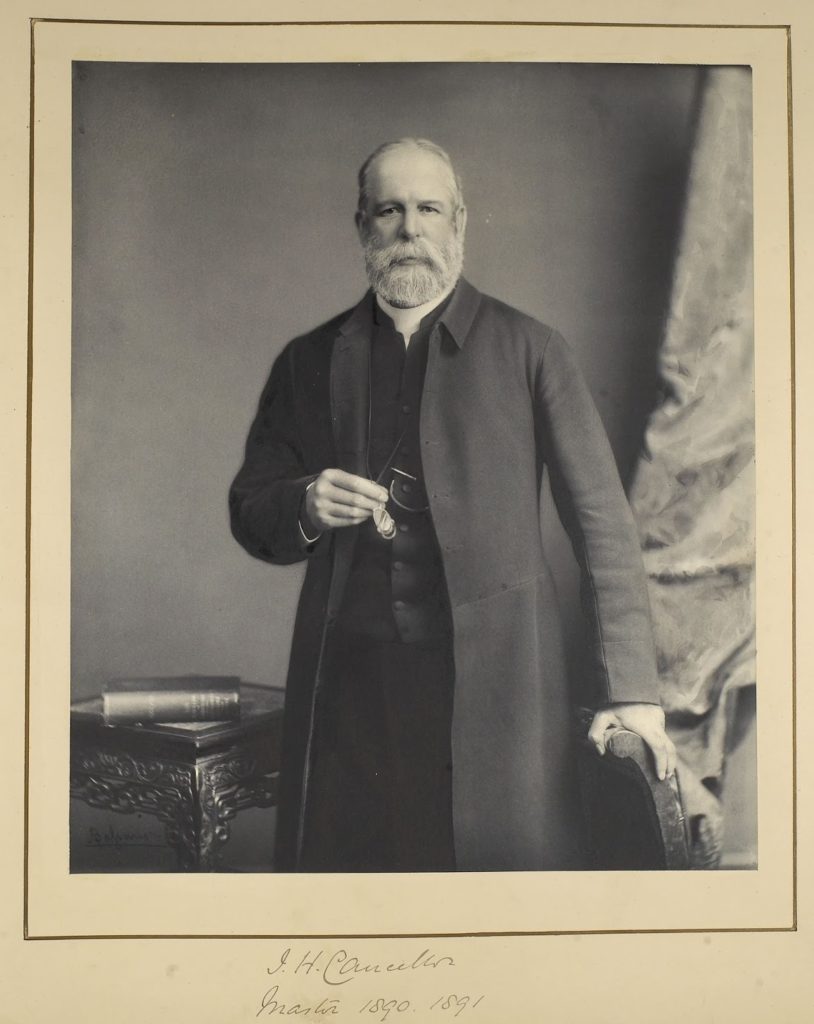

Reverend John Henry Cancellor was born in London in about 1834. His father, another John Henry Cancellor, was a Master of the Court of Common Pleas, and his grandfather had been a stockbroker. The family moved in monied circles.

Life was not plain-sailing, however. In 1856, Rev. Cancellor’s bankrupted uncle, Ellis Cancellor, tried to commit suicide by throwing himself into the Serpentine. And Rev. Cancellor’s youngest sibling, Reginald Channell Cancellor, “a particularly kind and affectionate boy, and very much attached to his father,” had what we would now call learning difficulties.

Rev. Cancellor was ten years older than his brother, so when, in late 1859, fifteen-year-old Reginald’s schooling became a problem, the older brother could step in with advice. Rev. Cancellor had been ordained as a deacon in 1857; as a respectable gentleman and a reverend, he decided to make use of his connections to help his parents school his brother.

He received a recommendation for Thomas Hopley’s school in Eastbourne. Hopley had grand ideas on educational reform; he had studied the education of industrial workers, and had written books on the subject. If anyone could manage Reginald, a boy who was seen as stubborn and lazy, who “would not readily do what he was told,” then surely it would be Hopley. And so Reginald was sent to Eastbourne.

Hopley didn’t like to use discipline on his pupils, unless it was deemed absolutely necessary. And with Reginald, it seemed that Hopley reached the end of his tether. When Reginald came home for the Christmas holidays, his father complained that too much violence had been used on him, but he did think that Reginald’s demeanour had improved.

In April, a letter arrived at the Cancellors’ home from Hopley, saying that Reginald had become obstinate again – and that he recommended the use of “extreme punishment” to force a permanent change in the boy. Hopley didn’t have a cane because ordinarily he didn’t like to use violence, so when Reginald’s father approved Hopley’s idea, the schoolteacher had to improvise.

With a walking stick and a skipping rope.

Who was R O Gilmore?

Among the many adventures I had writing Alfred Swaine Taylor‘s biography, I decided to track down the previous owner of a book.

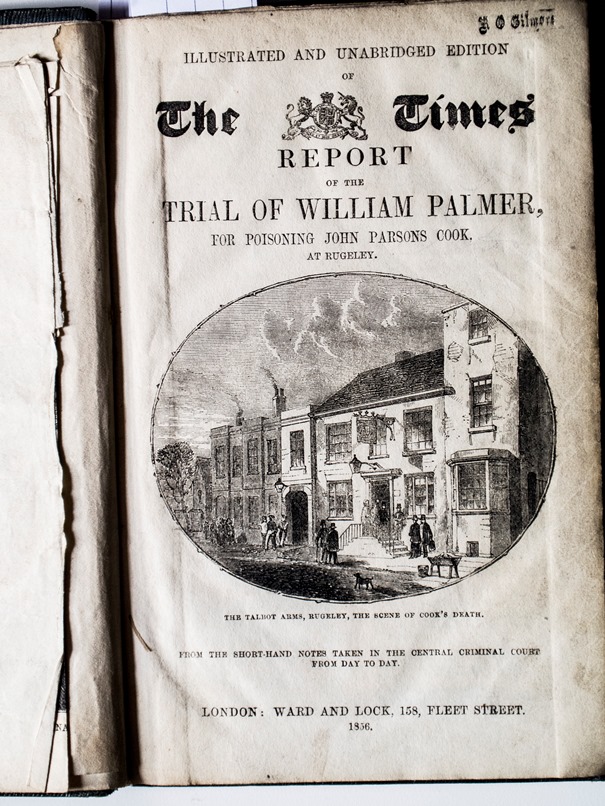

I work at a well-stocked library, and was able to borrow or consult most of the books I needed for my research. But I knew of two books on William Palmer which we don’t have, both of which were opportunistically cranked out by Ward and Lock just after the trial.

Their Illustrated Life and Career of William Palmer of Rugeley uses mainly old engravings which must have served time in many other books; only one of them isn’t a stock image, but is the portrait of William Palmer at the races which appeared in the Illustrated Times newspaper. The tale of Palmer is told in near-novelistic style.

Their other book, the frontispiece of which you can see above, contains transcripts of the trial at the Old Bailey, taken verbatim, and apparently nicked wholesale from The Times. It’s full of images which appeared in the Illustrated Times – which, despite the name, isn’t connected with The Times newspaper.

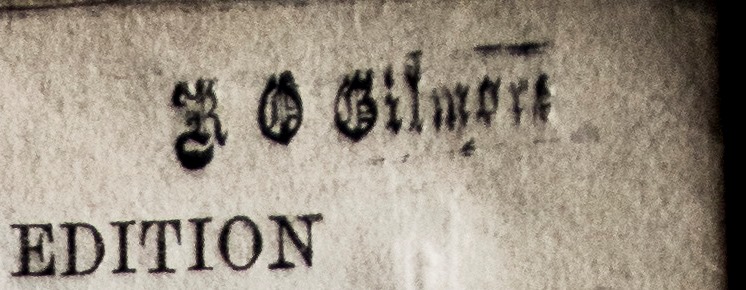

I managed to buy both books online, and most of the engravings in Fatal Evidence‘s plates section are from the Illustrated and Unabridged Edition. It’s a wonderful piece of history to have on my bookshelf, but I wondered, when I saw the neat owner’s stamp on the frontispiece, who was R O Gilmore?

The time I met a national treasure

I once, briefly, met actor and national treasure Robert Hardy. He died today, and the first thing I thought of was the fact that his booming voice has been silenced.

I grew up watching All Creatures Great and Small, and my friend and I enjoyed it so much that we used to “play vets” – she would be the vet, I’d assume a (I’m fairly sure, utterly dreadful) Yorkshire accent, and it was “Cow’s got them mastics, vet’n’ry!” all the way.

Hardy became an expert on longbows, apparently a side effect of playing Henry V. He did a lot of work with the Mary Rose Trust – Henry VIII’s favourite ship contains the oldest surviving English longbows.

At one point, my dad used to work for the Mary Rose Trust. I had to go to his office at the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard one day after school. I remember standing at the top of the stairs, staring about awkwardly at the Royal Naval-issue paintjob: matt duck-egg blue above and dark gloss navy blue on the lower half of the walls.

I saw a car pull up outside. I seem to recall that it was a Jaguar – possibly burgundy, or gold, but I do remember its distinctive personalised number-plate:

666 RH

Being a teenager, I laughed and pointed. That is, until I saw the driver get out.

It was Robert Hardy.

Real-life ecclesiastical sleuths: Reverend Wilkins & The Tragedy at Wix

Ecclesiastical sleuths are not unknown to crime fiction and drama – there’s Father Dowling, there’s G K Chesterton’s Father Brown, and James Runcie’s Reverend Sidney Chambers.

But what about in real life? A priest has a pastoral duty to their flock, and who better than a priest to try to grasp the effects of good and evil. Members of the clergy inevitably find themselves on the cusp of crime. Whilst they might have to counsel family affected by violence, do they ever join forces with the police and help to solve mysteries?

In my research of nineteenth-century crime I’ve found two clergymen who found themselves drawn into investigations. In part 1, you’ll meet Reverend Wilkins from Wix in Essex, who suspected that one of his parishioners had met his death “by unfair means”. And in part 2, read about Reverend John Henry Cancellor, who found himself investigating the suspicious death of his own brother.

Live Fatal Evidence Twitter Q and A

Fatal Evidence, my biography of leading 19th century forensic scientist Alfred Swaine Taylor, is published on Sunday 30th July. Join me between 12pm and 2pm BST on that day for a live Twitter questions and answers session. Use the hashtag #fatalevidence

If you don’t use Twitter, then worry not, you can ask a question on my Facebook too.

If anyone asks something that requires a long answer that Twitter won’t cope with, I’ll reply on here and link to it. I reserve the right not to answer all questions asked – I’m not about to suggest the best ways to bump someone off!

I look forward to speaking to you!

Bird image from The Graphics Fairy.

Strange history: BBC1’s Taboo

**SPOILER WARNINGS**

I was excited about BBC1’s gritty historical drama Taboo. After all, it was created by Steven Knight (the man behind Peaky Blinders, which I love), Tom Hardy and Hardy’s dad. Knight wrote it, as fans of Peaky Blinders will immediately spot – the troubled amoral “hero”, everything leading up to a nail-biting and very satisfying final episode. And I really loved the character Lorna Bow – an actress and young widow.

But I have to say that watching the series, I spent half the time entertained (sometimes when I should have been and sometimes when the concept’s daftness overwhelmed me – the Tom Hardy Grunt Counter springs to mind), and half the time feeling rather irritated.

I can’t help it. I know my history, and… well…. Shall we say that I identified a couple of historical errors, which, as someone who knows about these things, I really feel I need to point out.[1]There were other things I found rather… strange, but other people have written about those aspects. Such as, does Tom Hardy look convincingly like someone who is part white British and part … Continue reading

Footnotes

| ↑1 | There were other things I found rather… strange, but other people have written about those aspects. Such as, does Tom Hardy look convincingly like someone who is part white British and part First Nations? |

|---|

Endeavour and the crime scene photos that never were

Warning: for spoilers and dead people.

Television series Endeavour tells the adventures of young Inspector Morse, when he was mere Detective Constable Morse. I was late coming to this programme, but I have become completely addicted to it. Perhaps it’s the slightly grubby vision of the 1960s that fascinates. Perhaps it’s the puzzling plots. Perhaps it’s the portrayal of young Morse by Shaun Evans, who manages to include John Thaw mannerisms in his characterisation without looking as if it’s an impression.

There’s lots to love about it but one episode caught my attention particularly – “Nocturne”, in the second series.

Set in 1966 during the World Cup, there are flashbacks to 1866, when several children of a tea magnate, their nurse and governess, were murdered. Everyone thinks the murderer was the surviving daughter, who was, apparently, disturbed, and ended her days in an institution.

My interest was immediately piqued – nineteenth-century crime! – and when I heard the music, which was played on the piano and on the world’s creepiest music box, and was woven through the background music, I recognised it at once.

The piece of music is Chopin’s Nocturne no.1. It’s a beautiful piece for piano but it is intensely creepy and unnerving. It’s in B flat minor, which goes to some way to explaining it, plus the way that it keeps reaching for resolution and takes a surprising direction keeps the listener on the alert. This seems to be something to do with “picardie thirds” but that’s another story. It’s often peddled as a relaxing number – but I find it’s quite the opposite. It’s calm, but discordant, which makes it terrifying.

It was for this reason that last year, without having seen that episode of Endeavour, I used exactly the same Chopin piece for the Poison Panic book trailer.

So I’m not the only person to hear that nocturne and think of Victorian murder.

Ask Augustus

It’s not long now until my second book is published. Fatal Evidence is the first book-length biography of 19th-century forensic scientist Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor, MD, FRS. Readers of my first book, Poison Panic, may recognise his name, as will anyone who knows anything about Victorian crime.

Augustus, the professor’s assistant (well, ok, me in Victorian drag) will be filming a questions and answers session. It will go on YouTube, and any questions I don’t have time to answer in the video will be answered on this here website.

May I invite questions from all of you out there – who was Professor Taylor, why write a book about him, how can one identify Prussic acid in a dead person, and just what’s a chap to do when he finds a partial skeleton in a carpet bag? That sort of thing.

Don’t be shy. But don’t ask me What’s the best poison to kill someone with? Even if I knew, I wouldn’t tell you.

Please email your questions to [email protected] by Friday 16th June. (Let me know what name you’d like me to use. First name only, full name, your cat’s name, or random made-up name.)